“First initial. Last four of your social. Zip code.”

In January 2013, this was my supervisor’s daily greeting to all who visited the van. There was not one “type” of client. There was the man in business attire rushing to work; the old man too weak to leave his car unassisted; and the quiet housewife and hostess of a “knitting circle” for her friends.

As our clients dropped their used needles into our sharps container, we counted out an equal number of clean needles in exchange. We always offered other clean supplies for safe sex or safe injection. If they wanted to stop using and rehabilitate, we had resources. If not today, in the future, we told them. Just let us know when you are ready.

That was the long and the short of my internship with the then Free Clinic of Greater Cleveland’s Syringe Exchange Program (SEP). Looking back, I realize I assumed my role with next to no understanding of addiction, heroin use in America, or even what to anticipate of those who sought out SEP services. I thought clients might be irritable and even dangerous. Within minutes of my first client interaction, however, my apprehensions slipped away. Our clients were polite and brought New Years greetings along with their used needles. My experiences on the mobile unit of the SEP challenged me to think critically about the merits of harm-reduction programming through syringe exchange. I now appreciate that for anyone who has little personal experience with drug abuse or addiction it is difficult to value harm-reduction work. Arguments about how syringe-exchange programs enable people who inject drugs and that such programs muddy the message of the “war on drugs” can therefore seem plausible. Thankfully, there is substantial information available showing these programs are effective. It is important to realize that the innovation of harm-reduction work is critical and central to the currently evolving landscape of opioid and injection drug use.

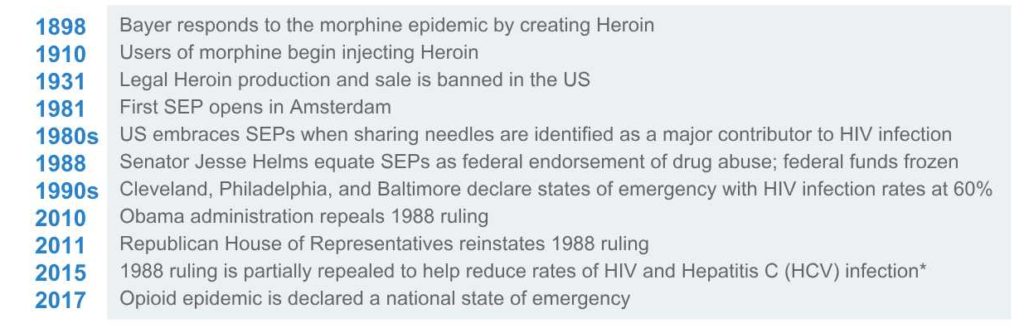

So what exactly is harm reduction? It is deceptively self-explanatory. For any behavior (e.g. drug use, sex), harm reduction is an approach to care that does not seek to change a person’s habit but make the activity they engage in less dangerous (1). More broadly, it is a social-justice movement focused on recognizing the autonomy and dignity of people who use drugs (2). The story of harm reduction as it relates to SEP begins with the introduction of heroin in 1898 by Bayer (3), the same company known today for its aspirin, according to the timeline below:

*Per the partial repeal of 1988 ruling, SEPs may function but federal funds are not authorized for the purchase of sterile syringes. Other harm-reduction programming and supplies can qualify for funding (4).

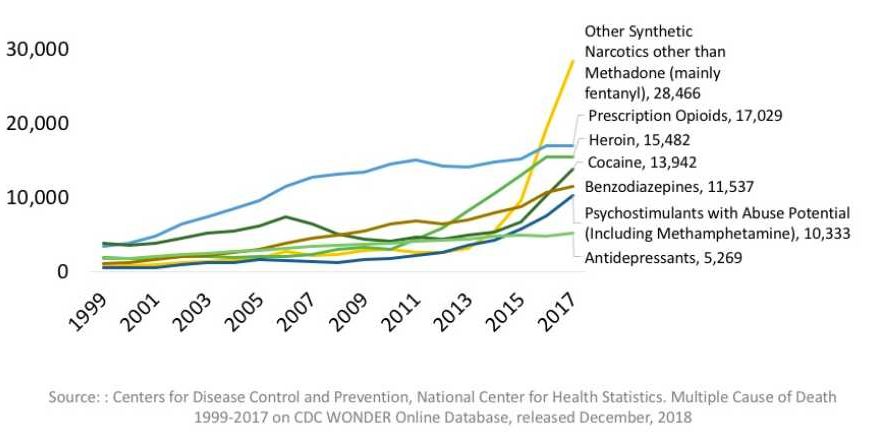

The need for SEP access is increasingly necessary as annual overdose deaths and HIV/HCV infections rise. A 2017 survey by the PewResearch Institute stated that nearly half of Americans had a close friend or family member with a previous or current addiction to prescribed or illicit drugs (5). Of the 47,600 opioid overdose deaths in the 2017, 33% involved heroin (6). As seen below, these drug deaths have more than doubled in two decades (7):

For those who inject drugs and share needles, there is the additional risk of HIV and HCV infection. In the 1990s, yearly cases of HIV infection were as high as 60% (8). While the national average for new HIV infections a year now hovers around 9%, there are several cities where that rate is higher, including Baltimore at 18% — despite SEP services (5). The New York Health Injection Drug Use Health Alliance found that SEP participants are about half as likely to share needles, while those who obtained them by other means (friends, family, shooting galleries) were three times more likely to continue sharing those needles (2). Several programs found that most regular clients live within a ten-minute walk of the site; those who live farther are less likely to make the trip (1). This can be problematic as studies have found that people who inject drugs largely do so publicly without proper syringe disposal (1,2). In addition to promoting the safety of those who inject drugs, SEPs also seek to protect the non-injecting community from harm. Programs hope that by incentivizing the return of used needles for clean ones, fewer will be left in public spaces where anyone – including children – can come into contact (9).

Sadly, injection drug use is increasing among younger cohorts, and this poses some ethical dilemmas. While working on the van, I was told heroin used to be the drug of rockstars and adults – never sold to children. Now, however, studies report use by children as young as 12 years old, with a national average of 1.7% of high schoolers having ever injected a drug (10). While demographics on heroin use by age and race vary by city, most identify heroin use predominantly among white, 18-25 year olds (2, 5, 11, 6). This is an abrupt shift. Prevention Point, an SEP in Philadelphia, calculated that new participants under 40 years old composed just 11.3% of their clientele in 1999. In 2014, that number rose to 58.7% (5). One Cleveland high school is locally known for its injection drug use and has been dubbed “Heroin High” (9). Despite this, most SEPs require a minimum age of 18 to participate, so some distressed parents, overwhelmed by their child’s drug use, end up seeking out clean syringes for them to use at home.

Though often politically criticized, harm-reduction efforts use innovation to access vulnerable populations. For example, in 2017, Nevada installed vending machines within harm-reduction agencies that dispense clean needles in exchange for used ones to registered clients (12). Anecdotally, in Hawai’i there are backpackers who hike to clients unable to reach traditional SEP sites. In Canada and in 11 other countries, safe-consumption sites (SCS) currently operate (5). These offer indoor environments where people can safely inject pre-obtained drugs with clean supplies under the supervision of medical staff. If clients overdose, staff administer naloxone. As seen with Canada, these sites have greatly reduced rates of overdose and new HIV/HCV infection without any effect on crime rates. These SCS are of great interest to several cities in the US, including San Francisco, Ithaca, Denver, and New York City. In 2018, Seattle and Philadelphia announced plans to open SCS (13). However, as of February 6, 2019, U.S. Attorney William McSwain declared his lawsuit to prevent the opening of the planned SCS in Philadelphia, arguing that this attempt to innovate would normalize illicit drug use (14).

Arguments against harm-reduction innovation should be weighed against the benefits. Studies clearly demonstrate how SEPs protect communities: ultimately, everyone is kept safe from accidental exposure to used needles that could otherwise introduce HIV/HCV infection. Further, SEPs train anyone interested to administer naloxone in the event of drug overdose (10). The problem of normalization arguably already exists, as evidenced by use of injection drugs increasingly among youth. SEPs also engage communities that are generally distrustful of traditional medical practices. With repeat encounters and consistent reminders of resources, many clients seek out treatment and rehabilitation, empowered by the trust, support, and lack of judgment by SEP workers.

SEPs are a symbol to people who inject drugs that their communities still care for their welfare and recognize their humanity. My supervisors in Cleveland knew most clients by name; they focused on developing relationships to lessen loneliness and aspired to help everyone seek rehabilitation and treatment. It is easy to criticize and seek to dismantle harm-reduction programming, but doing so only ensures the increased risk of harm, ranging from HIV/HCV infection to death. With half of Americans reporting they know someone with addiction to prescribed or illicit opioid drugs, we must realize these are our siblings, our parents, our childhood best friends, and our spouses; they need not only our compassion but the compassion of their communities.

Additional resources

- Harm Reduction with Crescent Care

- Harm Reduction with Trystereo

- Clean needle programs allowed under New Orleans City Council measure

- Good Samaritan Law (Act 392) allows people to call 911 for overdoses

References

- Allen TS, Ruiz MS, Jones J, Turner,MM. Legal spaces for syringe exchange programs in hot spots of drug use-related crime. Harm Reduction Journal. 2016;13(16). DOI:10.1186/s12954-016-0104-3.

- IDUHA. Harm Reduction in New York City. 2015. https://hepfree.nyc/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/IDUHA-Citywide-Study-Report-2015-3.pdf.

- Mckendry, J. Sears Once Sold Heroin: a very short book excerpt. The Atlantic, 2019. March. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/03/sears-roebuck-bayer-heroin/580441/.

- Weinmeyer, R. Needle Exchange Programs’ Status in US Politics. American Medical Association Journal of Ethics. 2016;18(3):252-257. DOI:10.1001/journalofethics.2017.18.3.hlaw1-1603.

- Larson, S, Padron N, Mason J, Bogaczyk T. Supervised Consumption Facilities – Review of the Evidence. Main Line Health Center for Population Health Research at Lankenau Institute for Medical Research. 2017;9-17.

- Valdez, AM. Will you save me? Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2019;45(1): 90-93. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jen.2018.11.005.

- National Institute of Drug Abuse. Overdose Death Rates. 2019. https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates.

- Hunt, D. Baltimore City Syringe Exchange Program, 2016. https://www.aacounty.org/boards-and-commissions/HIV-AIDS-commission/presentations/BCHD%20Needle%20Exchange%20Presentation9.7.16.pdf.

- Mcneil, G. Chico Lewis and Roger Lowe, Needle Exchange. Cover 2 Resources, 2016. https://cover2.org/episode-5-chico-lewis-roger-lowe-needle-exchange-part-one/.

- Klevens, RM, et al. Trends in Injection Drug Use Among High School Students, U.S., 1995-2013. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2016;50(1):40-46. DOI:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.026.

- Maurer, LA, et al. Trend Analysis of Users of a Syringe Exchange Program in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: 1999 – 2014. AIDS and Behavior. 2016;20(12):2922-2932. DOI:10.1007/s10461-016-1393-y.

- WBUR 90.9 Radio. Las Vegas’ Needle Exchange Vending Machines are a First in the US. 2018. https://www.wbur.org/hereandnow/2018/05/14/needle-exchange-vending-machines.

- Ghorayshi, A. There Are Now Two Cities In The US That Will Allow “Safe Injection Sites” For Heroin Users. Buzzfeed. 2018. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/azeenghorayshi/philadelphia-safe-injection-site

- Dale, M. U.S. Attorney sues over safe injection site in Philadelphia. ABC Action News. 2019. https://6abc.com/us-attorney-sues-over-safe-injection-site-in-philly/5124090/

Hannah Daneshvar is a second-year medical student at Tulane University School of Medicine in New Orleans. Prior to medical school, she worked in the non-profit and private sectors and volunteered with SEPs in Cleveland and New York City. This piece is inspired by her former SEP supervisors, who left a lasting impression on her with their drive to help their surrounding communities and their unfailing ability to recognize the humanity of every person they met at the van.