Society loves a good drug crisis. Even our current president Donald Trump knows that: “Drugs… have stolen too many lives and robbed our country of so much unrealized potential. This American carnage stops right here right now.” For decades, this “carnage” has provided politicians, parents, and pundits with a dependable scapegoat for just about anything. A potent mixture of crime, character flaws, and sensational health consequences, drug hysteria consistently delivers.

The 80s saw “the crack epidemic”, followed by horror stories of “meth mouth” in the early 2000s, and the craze of cannibalism-inducing “bath salts” a couple years later. That’s only in recent history. Prohibition, Reefer Madness, “this is your brain on drugs” as an egg is cracked into a frying pan – the list goes on. The latest drug hysteria is “the opioid epidemic”. However, opioid fear-mongering has been around since 1909, when Congress passed the Opioid Exclusion Act, outlawing the importation of smokable opium favored by Chinese immigrants (Gieringer 2009). Now, compared to the heroin surge of the late 1960s, new demographic populations are making the jump to heroin: in the 60s, 20% of users were female, 55% were white, and the average age of first use was 16; in 2010, over 50% of users were female, 90% are white, and the average age of first use was 24 (Economist 2014). This phenomenon has caused some researchers to question the sensationalism of the opioid epidemic and the public health focused approach – users are older, more commonly white females, and as such, policy makers have finally started to take notice (Hart 2016). Given the history of sensationalism surrounding recreational drug use, the notion that there is a problem at all should be rigorously questioned by the medical and scientific communities. Only 10% of any illicit drug use ever progresses into a substance use disorder, and opioid use disorder occurs in just 0.8% of the population (NSDUH 2017; SAMHSA 2017). Is “the opioid epidemic” just another political distraction or are there legitimate public health concerns?

To start, the term “opioid epidemic” needs unpacking. The CDC defines an epidemic as “an increase, often sudden, in the number of cases of a disease above what is normally expected in that population in that area.” (CDC 2012) Further, “opioid” encompasses synthetic drugs (e.g. fentanyl, tramadol), semi-synthetics (e.g. oxycodone, heroin), and “opiates” (e.g. codeine, morphine) naturally present in the opium poppy. Two things deserve to be clarified here:

- The real epidemic is the number of opioid-related overdose deaths: 75% of these overdoses involve the dangerous combination of an opioid and another respiratory depressant like ethanol or benzodiazepines (SAMHSA 2014a). Chronic pain patients often take several pharmaceuticals to manage their symptoms; without the proper patient education, medical use can readily become deadly. Patients/users who have built up tolerance to the analgesic and euphoric effects of opioids are more susceptible to overdose if they try to increase their dosage or potentiate it with other drugs. Dr. Nora Volkow, current director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, explains the physiology: “Tolerance to the analgesic and euphoric effects of opioids develops quickly, whereas tolerance to respiratory depression develops more slowly, which explains why increases in dose by the prescriber or patient to maintain analgesia (or reward) can markedly increase the risk of overdose” (P. 1256) (Volkow and McLellan 2016a).There is a strong need for harm-reduction education surrounding these fatal combinations.

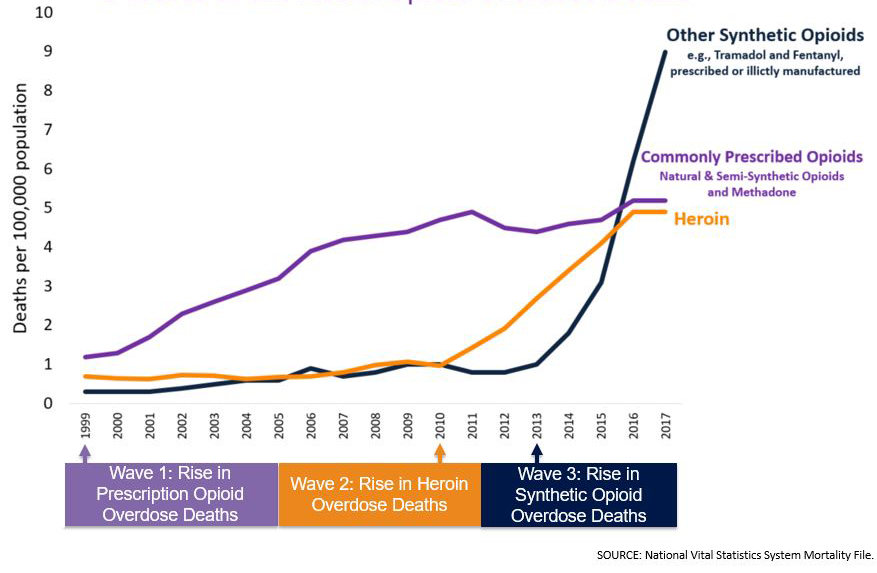

- There has been a sudden increase in the availability of opioids, but not all kinds at the same time: first oxycodone, then heroin, and most recently, fentanyl.

Three Waves of Overdoses

Levels of chronic pain have remained static since 1999, yet by 2012 opioid prescriptions and overdoses had nearly quadrupled (Rudd et al. 2016). In contrast, the American population, 273 million in 1999, had not even close to doubled – 322 million in 2016 (Schlesinger 2016; U.S.CB 1999). 75% of people who display opioid use disorder were not prescribed the drugs, so diversion is just as much of a problem as irresponsible prescribing practices (SAMHSA 2014b). However, the sheer number of opioid prescriptions makes diversion much more probable: “In 2012, 259 million prescriptions were written for opioids, which is more than enough to give every American adult their own bottle of pills” (Rudd et al. 2016).

Oxycodone

Why did opioid prescriptions start increasing in the first place? Enter OxyContin. In 1996, Purdue Pharma unveiled this opioid analgesic blockbuster, c.f. $31 billion over the past 20 years (Ryan et al. 2016). The pill was hardly novel – a controlled-release formulation of generic oxycodone. What was novel was their marketing (Van Zee 2009b). Addiction risks had long prompted doctors to restrict the use of opioids to cancer-related pain or terminal illness. Purdue touted OxyContin’s controlled-release preparation as less addictive. To justify this claim, marketing literature quoted a 1980 letter to the editor of The New England Journal of Medicine, which found addiction rates of less than 1% among acute pain patients treated with opioids in hospital (Porter and Jick 1980). This case report was not peer-reviewed, not controlled, not an article, in a hospital, acute versus chronic prescribing, etc. The true rate of iatrogenic addiction is much more ambiguous:

Although published estimates of iatrogenic addiction vary substantially from less than 1% to more than 26% of cases, part of this variability is due to confusion in definition. Rates of carefully diagnosed addiction have averaged less than 8% in published studies, whereas rates of misuse, abuse, and addiction-related aberrant behaviors have ranged from 15 to 26%. (P. 1259) (Volkow and McLellan 2016c).

This ambiguity was not reflected in promotional literature. Purdue’s target, the untapped “non-malignant pain market”(P. 187) (Purdue 1999), could be compared to a drug-naïve, recreational user transitioning to full-blown dependence: use started slowly, 670,000 patients in 1997, but escalated rapidly to 6.2 million patients in 2002 (Van Zee 2009b). Misleading data was not the only reason for this massive increase. Purdue’s revolutionary marketing tactics utilized prescriber data to target the most liberal prescribers of opioid drugs. These would be their dealers. Patient starter coupons reflected Purdue’s drug-dealing prowess: the first hit is free. Only in this case, it was more like the first seven to thirty hits, at which point the patient was usually opioid dependent (recent CDC guidelines for opioid prescribing have recommended curtailing opioid prescriptions to just enough medication for seven days). There were party favors for doctors too: emblazoned fishing hats, monogrammed stuffed gorillas, a swing CD called “Get in the Swing with OxyContin” – the DEA noted this was unprecedented for a schedule II narcotic (Van Zee 2009b). By 2002, 68% of oxycodone sales were through OxyContin, despite the availability of cheaper oxycodone generics that only differed in having to be administered more frequently (Paulozzi 2006). By 2004, more people non-medically used OxyContin than any other prescription opioid (Cicero et al. 2005). Perhaps the most telling statistic: “Among new initiates to illicit drug use in 2005, a total of 2.1 million reported prescription opioids as the first drug they had tried, more than for marijuana and almost equal to the number of new cigarette smokers (2.3 million)” (P. 224) (Van Zee 2009a).

What Purdue pulled off would not have been possible without friends. The “Pain as a Fifth Vital Sign” campaign was introduced in the late 1990s by the American Pain Society to address legitimate concerns over neglect for patient’s pain. Together with the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, the National Pharmaceutical Council, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, they successfully lobbied to change state regulations so that “no disciplinary action will be taken against a practitioner based solely on the quantity or frequency of opioids prescribed”(Optum 2016). In trying to plug a hole, the flood gates had been opened, and OxyContin was surging out. By 2011, the overdose death rate from prescription opioids began to level off, at which point it had nearly quadrupled since 1999 (Figure 1). However, the overdose rate from all opioids continued to climb, as a new player entered the scene.

Heroin

“Four in five new heroin users started out misusing prescription painkillers” and “94% of respondents in a 2014 survey of people in treatment for opioid addiction said they chose to use heroin because prescription opioids were ‘far more expensive and harder to obtain’”(Rudd et al. 2016). Indeed, heroin is very cheap and available. Just as substance use disorders perpetuate themselves by destabilizing people, drug markets thrive in destabilized regions. Six years after the war on terror began, opium (precursor to heroin) production in Afghanistan reached an all-time peak of 8000 tons – enough to keep the world’s opioid users high for at least a couple years (UNODC). At the same time, a narcotic synergy was building in Mexico. Newly elected president Felipe Calderón declared war on the drug cartels in 2006, relocating many drug patrols from the countryside to the cities. Previously, these patrols had patrolled Mexico’s mountain ranges, eradicating illicit poppy fields. With no one to stop it, opium production in the countryside increased tenfold by the end of the decade, from 5,000 acres to almost 50,000 (Wainwright 2016). It could not have come at a better time for the drug cartels. Any “Oxy” that doctors couldn’t or wouldn’t supply would be filled by this global excess of heroin, bringing its more dangerous routes of administration, unstandardized potency, and unknown purity, and subsequent increase in overdoses with it (Figure 1).

Fentanyl

The reasons for the increase in fentanyl availability starting in 2013 remains unclear – the rise of the dark web, increases in heroin seizures at the U.S. border, tacit acceptance of fentanyl labs by the Chinese government – the reasons are probably multifactorial, but someone in 2013 realized they could make a lot of money by rebranding fentanyl. It has been sold as counterfeit hydrocodone and oxycodone tablets, Heroin dealers readily increase profits (and overdoses) by cutting their product with it. Fentanyl is up to ~90x more potent than heroin (not to mention its analogues) and is readily available over the internet from China (DEA 2016, CDC 2017). Coupled with the rampant mislabeling of the drug, it’s easy to see why “other synthetic opioid” overdoses started rapidly increasing in 2013 (Figure 1).

Breaking the Cycle

Ruth Bader Ginsburg recently quoted a wise man, saying, “The true symbol of America is not the bald eagle; it is the pendulum, and when the pendulum swings too far in one direction it will go back.” Stringent opioid prescribing in the 80s and early 90s lead to the current crisis, and we run the same risk of history repeating itself if people who need opioids can’t get them. Doctors have known for a long time that opioids are addictive. They also know about harm reduction, and that opioids can be therapeutic. Neither Purdue pharma, nor the government should be telling doctors how to use these drugs. It’s up to physicians to find the middle ground.

Rod Paulsen is a second year medical student at LSUHSC-NO where he also received his Master’s degree for research on the neurobiology of opioid dependence. After medical school, he hopes to pursue psychedelic psychiatry for the treatment of addictions and psychospiritual distress.